The Show Must Go On: Jim Parks' benefit match - the last Championship match before World War Two

It should have been the perfect end to the summer.

The champion county, Yorkshire, was in town for Brighton & Hove Cricket Week and Sussex supporters were paying tribute to one of the county’s finest servants, Jim Parks senior, who had chosen it as his benefit match.

Jim’s son, Young Jim – he was seven at the time – remembers being taken to the County Ground to watch Dad in action on the second day of the game, a Thursday.

“The ground was pretty full even though it was a working day,” he recalled. “I remember being at the top end in glorious sunshine watching this great Yorkshire side with Len Hutton, Bill Bowes and Hedley Verity – all names I had read about or Dad had talked about - and thinking it was the most marvellous thing.”

The next afternoon Verity took seven wickets for just nine runs in 48 balls as Sussex were bowled out for 33. Verity, arguably the finest left-arm spinner English cricket has ever produced, would finish the last season of the 1930s as he had the first – his debut summer in county cricket - as leading wicket-taker with 191 victims.

At such an impressionable age, Jim was already in love with the game, but the reminders of a greater peril had never been far away in that summer of 1939. The senior basement playroom at his school, St Wilfrids in Haywards Heath, had been turned into an air-raid shelter and the pupils issued with gas masks.

*****

It says a lot about the players involved that the last game of cricket in England before the outbreak of the War was as competitive and hard-fought as it was, at least until the final afternoon when Verity wreaked havoc on a drying pitch.

A terrifying conflict was imminent – everyone seemed to appreciate that – but for the players and spectators it seemed more important than usual to have some vestige of normal life to enjoy before the onset of World War Two. The distinguished journalist RC Robertson-Glasgow wrote: “Cricket followers turned as to an old friend who gives you a seat, a glass of beer and something sane to think about.”

The Sussex Daily News page lead on Saturday September 2, the day before War broke out, began with the word ‘Lamentable.’ It was not a comment on the Sussex batting in the face of Verity’s brilliance or even Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s efforts at appeasement with Hitler. Rather, the word was used by the county’s chairman G.S. Godfree to describe the response to an appeal for funds in the club’s centenary year.

Sussex County cricket team, circa August 1933. Back row (left-right): Tommy Cook, Harry Parks, Jim Langridge, John Langridge, Jim Cornford, Jim Parks, George Cox. Front row: Maurice Tate, (unknown official), Ted Bowley, Robert Scott, Arthur Gilligan, Walter 'Tich' Cornford, Bert Wensley.

Sussex had distributed 15,000 fundraising ‘Centenary Cards’ and only 350 had been returned. “Something has got to be done about it,” remarked Godfree at the club’s annual dinner which still went ahead on that Friday evening at the Old Ship Hotel in Brighton.

“Some of us are getting rather tired,” he added. “If the people of Sussex do not want first-class cricket we will throw up our hands and they won’t get first-class cricket.”

Alongside it on the broadsheet page was a nine-paragraph report simply headed ‘Sussex All Out for 33.’

The dinner was attended by most of the Sussex players humbled earlier that day by Verity, including Jim Parks. He might have nodded sagely when his chairman made his remarks about the apparent lack of financial support for cricket in the county. In those days there were no benefit dinners or golf days, no auctions or wine-tasting trips which are the mainstays of the modern beneficiary’s calendar.

Instead, pre-War beneficiaries (and for years to come after it) would raise money paying visits to pubs and local cricket clubs and rely mostly on the generosity of working men.

“And in those days there wasn’t a lot of spare cash about,” recalled Young Jim. “If you came home from an evening doing a quiz or a talk at a pub with a few quid you’d had a decent night.”

The main fundraiser back then was the beneficiary’s match and in that regard Jim Parks had chosen wisely. Yorkshire were the team of the 1930s, having won the County Championship seven times. Only twice did the trophy leave Headingley during the decade – Lancashire won it in 1934 (a triumph that would take them 77 years to repeat outright) and Derbyshire were the champions two years later.

Yorkshire’s 1939 title completed a hat-trick of wins.

It was the last game of the season and, as Hugh Bartlett remembered, “the bands played on the outfield, the marquees were decorated and teas taken.” A collection for Jim on the final day raised £75 taking his total benefit to a princely £734. Today, that would be the equivalent of £36,000 – a sum most modern-day beneficiaries, even humble country pros, would hope to raise in a couple of events. At least Jim had the foresight to insure the match against bad weather for £250.

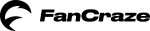

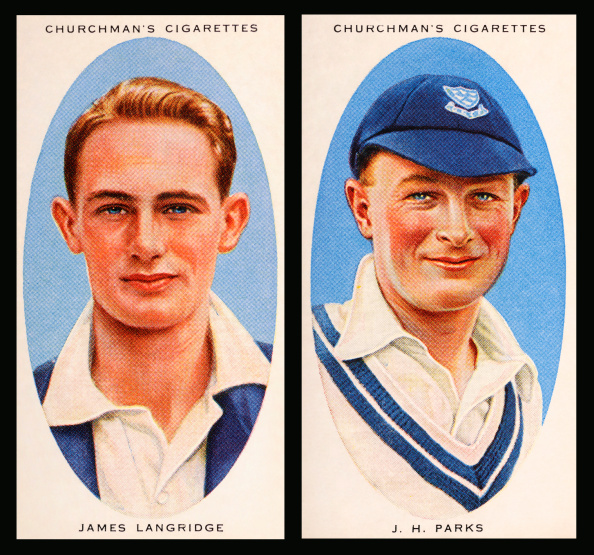

Vintage cigarette cards featuring, left to right, Sussex cricketers James Langridge and James Parks, circa 1936.

These days, the distraction of running a benefit is often given as a reason why players underperform on the pitch. A convenient excuse perhaps, but there could be little other reason to explain why the summer of 1939 was one of Jim Parks’ poorest in a career which brought him more than 21,000 first-class runs including 41 centuries.

He had done the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets for the first time four years earlier and in 1937 he threw himself into his cricket after his wife Irene had died of tuberculosis in October 1936. That summer he scored 3,003 runs and took 101 wickets with his off-cutters and in-swingers. His form earned him an England cap when he opened with a young Len Hutton at Lord’s against New Zealand.

A mainstay of the Sussex side for more than a decade, Jim turned 36 a few weeks after the 1939 season began. Perhaps age was beginning to take its toll. In 1938 Jim still scored 1,740 runs at 37.82 including four hundreds, but his benefit season brought him 1,108 runs – his lowest aggregate since 1932.

He averaged a modest 24.08 with only one hundred, although he still played in 31 first-class games and his place in the side was never in doubt because he could still contribute with the ball. That season he took 83 wickets, his third-highest return in a career now into its 16th season.

Any hopes that Sussex might celebrate their 100th anniversary with a tilt at Yorkshire’s supremacy didn’t last long. They won ten games that year, including four in August, and finished tenth but the best days of a side which had finished runners-up three times earlier in the decade were clearly receding.

Jim’s best performance of the year had come with the ball when he took 5 for 27 against Gloucestershire at Bristol. His only hundred was against Worcestershire at Eastbourne nine days before his benefit game when he made 115 not out in an eight-wicket win.

“I was there for that game,” remembers his son. “John Langridge hit out on the last afternoon and Hugh Bartlett won us the game in the final hour.”

In contrast to Sussex’s stuttering form, Yorkshire had swept all before them. Hove was the last stop on a southern tour that had begun at Dover where Verity took nine wickets as Yorkshire won after being put in.

“At Dover, the outbreak of War seemed imminent every minute,” wrote the doyen of Yorkshire cricket chroniclers Jim Kilburn. “Boys came to the ground with telegraphs almost in procession with orders for reservists to report for duty. Cricket was a secondary topic among players and spectators.”

Yorkshire then travelled to Bournemouth where they twice bowled out Hampshire for 116. Verity took 6-22 in the first innings and Yorkshire, who had made a modest 243, still won by an innings.

By now, the country knew war was inevitable. Yorkshire batsman Herbert Sutcliffe, a reserve officer, headed back to Yorkshire instead of along the south coast for the season’s finale after being called up. Skipper Brian Sellers called his squad together and they decided to play the game at Hove, not least because they didn’t want to let down Jim Parks.

“We are entertainers and until we have had instructions to the contrary we will carry on,” he insisted.

It wasn’t a sentiment shared by the rest of the cricketing world. With seven games of their tour still to play, the West Indies sailed for home. Other county games were called off and the Scarborough Festival was cancelled.

As German forces massed on the Polish border, Sussex versus Yorkshire began as scheduled at 11.30am on Wednesday, August 30 1939, and a crowd of 4,000 turned up for the first day in glorious sunshine.

In The Times, Dudley Carew wrote: “Hove was crowded, but nothing like as crowded had there been no threat to Poland. Groups of people gathered around cars parked in the ground listening to the wireless as it spoke of the hopeless, last-minute efforts to save a peace that was beyond aid.”

Jim Kilburn was another scribe trying to concentrate on the matter in hand. “The weather behaved itself most admirably for the opening of the benefit match for James Parks,” he wrote in the Yorkshire Post. “A considerable number of guests (paying guests of course) broiled upon the benches, sheltered in the stands or lay scattered on the grass to watch cricket of unfailing interest. Cricket for cricket’s own sweet sake, with Championship cares dead and buried.”

Jack Holmes won the toss and Sussex made 387, the highest score against Yorkshire that season. In keeping with a disappointing summer with the bat, Jim Parks made just two coming in at No.6 but Sussex were sustained by a brilliant innings from George Cox junior with even Verity struggling to tame him.

He came in with Sussex 89-2 after Cox had added 69 with John Langridge before Langridge was run out for 60 when Cox drove Verity to mid-off, set off for a single and turned to see his partner run out by Barber’s direct hit. “In the afternoon, Cox expressed his apologies clearly and handsomely,” wrote Kilburn.

James Langridge and Parks both fell cheaply but Cox and Hugh Bartlett added 61 for the sixth wicket. Cox was well into his stride now, hammering the bowling to all parts. He scored 28 in ten minutes after lunch to reach his half-century and his hundred, which he reached just before Bartlett was bowled for 24, came in two hours, 10 minutes.

Even Verity was harshly treated. Cox, demonstrating the muscular hitting his father had occasionally employed in Sussex’s lower order, smashed him high over long on for six. That year, the Championship experimented with eight-ball overs and in 18 of them, Verity conceded 108 runs before picking up the wickets of Holmes and Billy Griffith towards the end.

Members of the Sussex County Cricket Club during their first official practice at the nets in their club at Hove, UK, 25th March 1935. From left to right, Albert Wensley, Jim Hammond, Harry Parks, John Langridge, Bill Greenwood, Tich Cornford, James Cornford, Maurice Tate and James Langridge.

The innings was not all about brutal power. “Elegant cuts and some extremely fine-placed shots just wide of third man helped provide him with a total of 198,” reported the Sussex Daily News.

Dudley Carew was equally impressed in The Times. “Concentration on the cricket was fitful yet Cox’s strokes through the covers insisted on drawing attention to themselves. They were played in the grand manner and again and again the ball came rattling up against the pavilion rails.”

The sagacious Kilburn, not used perhaps to seeing his beloved Yorkshire put to the sword, was a little more guarded in his praise. “At times Cox knew fortune, but then his method invited the co-operation of fortune. When he could not reasonably drive he was prepared to cut and if the slips once or twice stretched up expectant hands, many of the boundaries gathered were as faultless as they were beautiful.”

The sight of Cox in full flow was to become a familiar one for Kilburn and the Yorkshire team for young George loved batting against the White Rose, the challenge of facing the best county attack of his generation seeming to bring the best out of him.

In 1938, Bartlett had taken 157 off the Australians that included a 57-minute hundred that put him in contention for the Walter Lawrence Trophy, awarded for the fastest century of the season. The next game was against Yorkshire when Bartlett, who was not playing, was presented with a gold cup for the quickest fifty of the summer before the start of play.

Cox took up the challenge of outscoring Bartlett, encouraged it seems by Sutcliffe, Yorkshire’s prolific opening batsman. Having watched the ceremony, Sutcliffe remarked to Sussex secretary Lance Knowles: “It’s not the end of the season yet, there is young George remember.”

With Langridge occupying the sheet anchor role, as he had done for Bartlett against the Australians, Cox went on the offensive against an attack including Verity and Bill Bowes. His 50 came in 28 minutes and 25 minutes later, he had moved onto 95 with some savage hitting. Six runs in three minutes and the Lawrence Trophy would be his.

Maurice Leyland came on and bowled a rank long hop. “I could have hit it anywhere,” remembered Cox. Instead, he mishit out into the deep and Wilf Barber ran around the boundary to restrict him to a single. Langridge got out and skipper Holmes, urged by the crowd to get a move on as he made his way to the wicket, came in but time had beaten Cox. He duly got to three figures, but that missed six and the fall of Langridge’s wicket had taken up too much time. His hundred took three minutes more than Bartlett’s.

Of his 50 hundreds for Sussex, six came against Yorkshire including 212 and 121 (both not out) in 1949, 143 in 1950 and 144 in 1953. Cox rated that 1938 performance as his finest innings for Sussex, better than his 198 a year later when a Hove crowd desperate for a pleasant distraction lapped up the entertainment.

“War was upon us,” said Cox, “And it was no longer possible to ignore the War bulletins. The guns had started in Poland and the tension was awful. There was a feeling we shouldn’t be playing cricket but there was a festival atmosphere. We knew that this was to be our last taste of freedom for many years so we enjoyed ourselves while we could.”

The Sussex faithful dug deep when the tins were rattled as a collection for the beneficiary at tea raised £75. “Please give them a big thank-you,” Parks told the man from the Sussex Daily News. “Not only was I surprised at the size of the crowd but also for the magnificent support for the collection on my behalf.”

The celebratory mood continued. A few moments after Sussex had been dismissed for 387, it was announced that Cox was to marry his sweetheart Eve Ansell in the family church at Warnham the following month, to warm applause from the spectators.

“Had Jim Parks been a magician he could not have staged his benefit match to better purpose,” said the Sussex Daily News. “Brilliant weather, a wonderful 198 from Cox and a big crowd were a joint tribute to a fine cricketer.” Of Sussex’s last 121 runs, Cox contributed 90 of them. He was ninth out when he square cut the off-spin of Ellis Robinson to the gully, the innings ending off the next delivery.

Jim Parks, Sussex County cricket club, circa 1933.

Before the close, Yorkshire had reached 112-1 in reply in 75 minutes. Ominously for Sussex, Len Hutton was unbeaten on 55.

In the early hours of Thursday morning the good weather broke and Hove was hit by heavy rain. With only the wicket-ends covered, the pitch took a good soaking. There was no chance of an immediate resumption on the second day yet a crowd of 2,000 still turned up and Parks’ benefit coffers were enhanced by a collection which raised another £26.

The War news remained grim. Holed up in their hotel while they waited for a break in the weather, the Yorkshire players fretted. “All through the morning in our hotel we were anxiously discussing the cables from Poland and Germany, which made it plain a world war was just about to begin,” said Norman Yardley. “We managed to restart the game but it was played with many men’s minds elsewhere. But to Yorkshiremen, cricket is cricket and when we get out on the field our job is to win the game, no matter whether the heavens are falling.”

The heavens having opened and done their worst, play resumed at 3.30pm and Hutton and his partner Arthur Mitchell had little difficulty against a modest Sussex attack, although Mitchell’s 14 runs in the first 50 minutes suggests batting initially was not easy, particularly against Jim Langridge’s under-rated left-arm spin and Parks himself.

“Conditions were entirely altered,” wrote Kilburn. “Whereas on day one the ball had come through comfortably and according to reason now it moved sluggishly from the pitch and at varying and illogical heights.”

Hutton, one of the finest players on drying surfaces, soon worked out what to do.

Yardley recalled: “Len came down the wicket to Langridge, drove and pulled, square-cut and late-cut when he changed his length, and we were edified by the sight of a great bowler on a heaven-sent wicket being slammed all over the place.”

While Mitchell settled for quiet accumulation, Hutton was soon racing towards his 12th century of the summer. In two hours 15 minutes, Hutton made 103 with 14 boundaries and it was a surprise, not least to the bowler himself, when he missed an attempted sweep and was trapped leg before by Cox, the fifth bowler used by Sussex. Mitchell, Maurice Leyland and Yardley all made half-centuries either side of tea and when stumps were drawn shortly after 7pm, Yorkshire’s reply had reached 330-3, 57 runs behind with a day to go.

The mood of the country remained grim. A couple of Friday’s newspapers made optimistic claims that War could still be avoided, but the people sensed otherwise.

Early in the day, Lancashire’s match against Surrey at Old Trafford was abandoned and matches due to start that morning were also called off. The Yorkshire committee sent a telegram to captain Sellers suggesting they pull out and head home early. Sellers’ response was that as it was Parks’ benefit they would prefer to continue. His club reluctantly agreed.

Under a blazing sun, Yorkshire’s first innings folded alarmingly. As a portent for what was to come, Langridge recovered from his second-day mauling to take four wickets. Parks himself chipped in with three. Yardley made 108 but Yorkshire lost their last seven wickets for 62 runs and their first-innings lead was a slender five runs.

It was now that Verity got to work. During the ten seasons of his first-class career which spanned the Thirties, he took 1,956 wickets, 83 of them against Sussex at an average of 17.42. Opening the bowling at 12.15pm, he struck first ball when Parks was trapped lbw having elected to go up the order because Bob Stainton was nursing a leg injury. Verity’s new ball partner, Ellis Robinson, had John Langridge taken at short leg and 12-2 quickly became 13-4 as Verity claimed Harry Parks and James Langridge in his third over.

Cox was now joined by Bartlett, who remembered Verity’s remarkable performance.

“The light billowing clouds of mist which often curled in from the sea at Hove were absent on the day of Hedley’s last cricket triumph. There was a blazing sun and the wicket was ready for Hedley. It really suited him but you have got to be a good enough bowler to take advantage of it, which he did to our cost.”

The wicket was cutting up badly as it dried out. Bartlett, Holmes and Griffith – the four amateurs in the Sussex side – were soon out, all bowled by Verity. At 25-7, there was little hope for the county. Cox would later claim that he top-scored in both innings after making nine to add to his 198, but Harry Parks made the same score. The tail failed to wag and in just 11.3 overs the innings was over – Sussex all out for 33, Verity finishing with 7-9 from six overs with one maiden.

“Verity bewildered, confused and confounded the enemy so completely that no batsman had time or opportunity to make double figures,” wrote Kilburn. “The wicket was perfectly suited to spin bowling but the Sussex batsmanship was of the feeblest.”

There is no doubting the quality of Verity’s craft, but Jim Parks junior believes that for the first time in the match Sussex minds, inevitably given the circumstances, were elsewhere.

“Dad always talked about Hedley Verity in glowing terms but that match was played in quite a surreal background. It’s amazing that they played at all in the circumstances but they wanted to give Dad the chance to make a few quid.”

Verity seldom courted publicity or tried to elicit praise for his endeavours on the cricket field although he seems to have been aware of the significance of the match, if not necessarily his performance in it. “I took the congratulations of the Sussex players, but I wondered if I would ever bowl at Hove again.”

There was a last twist as Yorkshire set out to score 29 for victory. Hutton needed seven runs to beat his previous best aggregate for a season of 2,888 runs set in 1937, but made just a single. The champions nonetheless gained their 20th victory of the season just after 2.30pm by nine wickets.

An hour or so later the Yorkshire team was back on their Southdown motor coach and heading home, Kilburn among the passengers.

“There was no guessing precisely what the future held, but there was no escaping the reflection that a much-loved way of life was being shattered, perhaps beyond repair,” he wrote. “Scarcely anyone mentioned the cricket, though the past few days had brought cricket of uncommon quality.

“We reached the outskirts of the capital and for a mile or two the route led down the Great West road towards London. In that direction there was no other traffic but the opposite path was crowded to danger point with every conceivable kind of vehicle carrying every conceivable cargo. Coach-loads of children swept to unknown foster homes. Urgency covered the earth.”

At 6pm, barely four hours after Verity had spun Yorkshire to victory, Germany invaded Poland. Because of an experimental night-time blackout, the Yorkshire players stopped for the night at Leicester but continued their journey soon after dawn.

“Finally came journey’s end in Leeds City Square,” wrote Kilburn. “Thence departed their several ways one of the finest county teams in the history of cricket. It never assembled again.”

Bill Bowes recalled how that Friday night he had spent long hours discussing the prospect of War with Verity and what they should do. In the end both joined up. Bowes took part in the North Africa campaign as a gunnery officer, Captain Verity accepted a commission into the Green Howards regiment.

In July 1943, he was seriously wounded by mortar fire during an attack on enemy positions in Catania on the island of Sicily. Captured by the Germans, he was treated for his wounds and then handed over to the Italians at the military hospital in Naples. An operation to remove part of his rib which was pressing down on his lung was successful but he died on July 31 1943.

There was a poignant post-script to Verity’s last wickets at Hove. In the first match of the opening post-War season in 1946, Yorkshire captain Brian Sellers put his hand into the top pocket of the blazer he had last worn at Hove nearly seven years earlier and picked out a tiny slip of paper.

“Good God Norman, look at this,” he said to Yardley. It was the scorer’s chit, handed to him by Yorkshire scorer Billy Ringrose at Hove on September 1 1939. The figures were faded but still legible. They recorded Verity’s final bowling analysis – 6-1-9-7.

Two days after Verity had spun Yorkshire to victory Jim was at his grandmother’s to hear Neville Chamberlain’s fateful midday broadcast to the nation that Britain was at war with Germany. As father and son walked home in the late-summer sunshine they heard the air-raid sirens for the first time. For the next six years there would be no competitive cricket. The Second World War robbed great players of some of the best years of their career. Some, like Verity, made an even bigger sacrifice.

Sussex County cricket team, circa May 1937. Back row (left-right): EH Killick (scorer), Harry Parks, George Cox, John Langridge, Jim Cornford, Charlie Oakes. Front row: Jim Parks, Maurice Tate, Jack Holmes, Walter 'Tich' Cornford, Tommy Cook, Jim Langridge.

Jim senior was 36 when War was declared and, like Verity, probably knew that he had just played his last game of county cricket. He moved to Lancashire on police service and began playing in the Lancashire League for Accrington and in the Northern League for Blackpool, both competitions having carried on despite the hostilities. Jim could look back on a Sussex career which brought him 19,720 runs, the best 197 against Kent, and 795 wickets. Between 1927 and 1939 he passed 1,000 runs on 12 occasions.

When his playing days were over he moved to Trent Bridge to become Nottinghamshire coach and even at the age of 54 was playing second XI cricket. But in 1963 he returned to Hove as Sussex coach before a stroke forced him to retire, although he remained a regular visitor to the County Ground before his death in 1980.

Apart from Lord’s, nowhere was Wartime cricket played more regularly than Hove.

In 1942, there were regular games on Wednesdays and Saturdays and with service teams using the County Ground frequently some of the greats of the world game enjoyed the welcome distraction of a game by the seaside, including Keith Miller, Denis Compton, Alf Gover, Gubby Allen and Trevor Bailey.

On one occasion during a match between the Home Guard, who were stationed at the County Ground, and a Sussex XI to raise money for the Spitfire Fund Spen Cama - whose generosity after his death funded the redevelopment of Sussex’s headquarters - John Langridge, Maurice Tate and Arthur Gilligan were among those who ignored two air raid sirens to play on.

Only when a German bomber banked and scattered two bombs on the ground did they finally run for the shelters. One landed on the old squash club, the other in the south-east corner of the ground. Neither device exploded. That determination to carry on the game, so evident in 1939, had prevailed again.

This piece originally featured in Bruce Talbot's fantastic book, Sussex CCC Match of My Life. Bruce has also worked with former Sussex captain Ian Gould on his autobiography, Gunner, which is out now and published by Pitch (£19.99).